Through Western Spain from Galicia to Andalucia

It is easy to spend a lot of time doing not a lot on the Costa del Sol. However, there are still quite a few areas of Spain Ted and I haven’t explored. The plan for this trip was to travel from North to South through Western Spain avoiding Madrid – which can be tricky as most rail journeys lead to the capital. This journey took place in March 2016 so hot weather was unlikely to be a problem – when I checked the weather we had just missed some serious winter weather in Galicia.

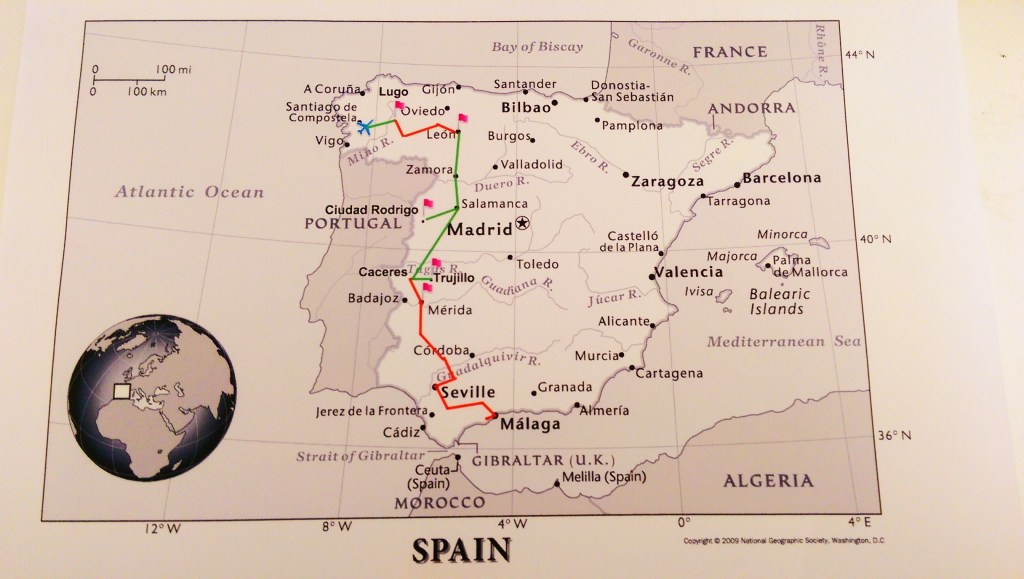

I found a cheap flight to Santiago de Compostela which determined the starting point. The plan was to avoid places I had been to before, travel by train and bus, enjoy the journeys and the places we stop and have a few beers along the way. After some research I settled on a six-day route taking in overnight stops in Lugo, León, Ciudad Rodrigo, Trujillo and Mérida. On the map below journeys by bus are in green and by rail in red. More recently, in May 2023, we spent a night in Mérida en route from Málaga to Portugal and I made a few minor changes as a result. In late 2025 the page was updated – many more photographs have been included and travel information has been brought up to date.

Following the account of our trip we have provided additional information – Railway Buffery for those interested in trains, the hotels we used and travel information. At the end of the page are the notes mentioned in the text and links to other pages on the site which may of interest to those planning to travel in this area.

Galicia

The trip began with a Vueling flight from Málaga to Santiago de Compostela. The flight was almost full and I didn’t have a window seat – on this occasion it would have been worth paying for a specific seat as it was a clear day and a new route to me. There are about ten air-bridges at Santiago, yet we were the only plane in the whole airport. The departure screens suggest that it is busier later in the day.

Having visited Santiago de Compostela twice before I looked for somewhere else in Galicia and came up with Lugo. Lugo is the capital of the Galician province of the same name and has about 100,000 inhabitants. It was the Roman settlement of Lucus Augusti, and the main attraction today are the Roman walls, a UNESCO World Heritage site. According to Wikipedia, Lugo is the ‘only city in the world to be surrounded by completely intact Roman Walls’, so worth a visit.

Ted goes for a wander round the Roman walls in Lugo

It may have been a clear day but it was also cold – it was only 7ᵒC outside so I hung around the terminal until the bus was due. Lugo is 90 kilometres from the airport, about 1hr 45mins on the bus. We drove through wooded hills on the old national road. An autovía was being built but remains incomplete in 2025. This was a stopping bus, so we passed through the towns and villages en route. Towns such as Arzúa, Melide, Palas de Rei, Guntín are all built on hilltop sites and the housing is typically Galician – blocks of flats with glazed-in balconies and corrugated iron gables. The street signs are in Galego, so there are plenty of ‘x’s in the names. Every village and town has a pulperia or two, specialising in serving octopus.

The agricultural areas have tiny farms and fields. Many of the rural houses have small rectangular barns or granaries (hórreos) on pillars raised off the ground. They are smaller and more rectangular than those I’ve seen in Cantabria or Wallis (Switzerland) but presumably have the same purpose, to keep grain dry and free from mice and rats (see Note 1). Even some new houses had built modern concrete or brick versions. The road was largely empty of traffic, even on the short sections of autovía that we used.

At Santiago airport there were a few pilgrims with their wooden staffs, having completed their pilgrimage on the Camino de Santiago (Way of St James). We regularly passed the scallop signs indicating one of the routes, all of which lead to the shrine of St James in Santiago de Compostela. The shrine was a major pilgrimage destination in the Middle Ages, matched only by Rome and Jerusalem. After several centuries when there were few pilgrims, due to war or epidemics, the routes were designated UNESCO a World Heritage Route in 1987 and have since been promoted as a major tourist attraction. The main route from the French border passes through Galicia to the south of Lugo, via the towns of Melide and Arzúa, and it is easy to see the tourist infrastructure which the route has created, bringing jobs to a remote area of Spain (see Note 2).

Lugo

The city sits on top of a steep hill above the Rio Miño and its tributaries. To reach the bus station we gain height by going round the streets of Lugo in what seems like circles. In common with many places the bus station is a particularly grotty introduction to the town. When I get my bearings it seems we are in the Praza de Constitución just outside the city walls. It is possible to walk the complete circuit along the top of the Roman walls – more than 2km – and they are impressive. There is a main road encircling them (which makes photography without being run over difficult, but at least it means the centre of town is largely traffic free) and we walked round them to gain an idea of the layout of Lugo. Within the walls the old town is a mixture of medieval and eighteenth century buildings, some well looked after, others in serious disrepair. There’s some regeneration going on close tothe walls but still a significant number of derelict buildings. To reach my hotel we walked to the Praza Maior via the Rúa Nova and the cathedral. Rua Nova has plenty of restaurants and bars so there was time for a quick beer.

Arriving in Spanish towns and cities in mid to late afternoon after a day’s travelling gives one the impression that everything is shut – there is hardly a soul around. This happened every day on the trip. The temptation is to think that the economy of the town is suffering badly and it has been semi-abandoned. It is true that there are often empty shops and derelict buildings in the old centres, due to the recent move outwards to modern suburban flats and the construction of out of town shopping centres. However, go out about six o’clock and everywhere is packed, the shops and streets are busy and it is clear that you have exaggerated the problem.

We checked into the hotel, where Ted and I were given a suite with not just one but two balconies. After a brief rest we headed out for general wander around and to find a basic food shop for some odds and ends for our journey. I eventually managed to find a small supermarket in amongst the vast numbers of shoe shops. Why are there so many? Then it was time for a few drinks and pinchos. Even on a Monday night the bars were fairly busy. Some nice tapas, including empanada and popcorn (separately) in Cerveceria Lua, which had a selection of craft beers in bottles – I tried a Portuguese red ale and some Santa Cristo APA, brewed in Galicia at Ourense. I tried a few other places and enjoyed myself – helped by the fact that most people spoke pretty clear Spanish and it was much easier to follow some of the conversations than it can be in Andalucía.

Lugo to León

Breakfast was included in the hotel so I fought my way through the horde of Spanish pensioners on their Social Security holiday and filled myself up. It was a cold and misty morning as we made our way down to the station. The 1110 Alvia train from Lugo to Madrid was hauled by hybrid locomotives which can operate either on diesel or electric power. We’re away from the main lines here – despite being a sizeable provincial capital the train was quiet and the next departure to anywhere was at 1924. The first stage was to Monforte de Lemos. We quickly left Lugo behind as the new blocks of flats on the slopes give way to countryside. A few kilometres outside Lugo there were signs of a new section of double track line being built – we hoped the investment meant that there was a plan to increase the service from the 2016 timetable of 5 trains a day (2 of which were overnight). 2025 update – the service has vastly increased to 8 trains a day (none overnight) and the daily train to Madrid departs at 1118. The mist cleared and the countryside felt quite remote until we approached the town and railway junction of Monforte de Lemos (See Railway Buffery 1 for more about the railways from Lugo to Leon).

The connecting train to León was one of the remaining examples of a traditional long distance Spanish train (most have been replaced by the high speed AVE trains). The loco and five coaches are on route from Vigo and A Coruña to Bilbao and the French border at Irun/Hendaye. It was quiet, though the few passengers (including the only baby who sits behind me and enjoys kicking the seat-back) have been allocated seats together by the Renfe (Spanish railways) computer, as usual. The conductor checked his reservations and allowed us to spread out. In 2016 the 1 daily train linking these cities took 11 hours 59 minutes for the 884km from Vigo to Hendaye (you can see the publicity now – ‘across the breadth of Spain in less than half-a day’). There was no buffet, but the broad Spanish gauge meant the train was roomy and comfortable, and the sedate speed allowed a good look at the landscape. In 2025 the only option to Leon is to depart Lugo at 0855 and change at Monforte de Lemos – the Leon train continues to Barcelona arriving there 13 hours 51 minues after departing Vigo. Spain has more high speed lines than any other country in Europe, giving much faster journeys, but direct routes, extensive tunnelling and high speed means that some of the traditional benefits of travelling by trains such as this have been lost.

And the landscape was interesting. For much of the journey the line follows the valley of the Rio Sil (a major tributary of the Rio Miño – the northern border between Portugal and Spain). The first stretch is through a gorge which has been dammed to produce hydro-electricity. The first stop is A Rúa-Petin and from there to O Barco the valley is broad and there are signs of mining and industry as well as vineyards and poplar groves (see Note 3). Finally, we left Galicia and entered the region of Castilla y Leon.

Just over one and a half hours from Monforte de Lemos we arrived at Ponferrada, the largest town en route, where the Rio Sil turns westwards from its source in the Cantabrian mountains to the north. The buildings have changed, with none of the Galician touches, and all the signs were written in standard Castellano Spanish. Though there is a castle visible from the railway line it is clear that Ponferrada was mainly an industrial centre, with the ruins of works and mines still visible. Alongside the railway are derelict goods yards and factories, including a row of rusting stream engines. From Ponferrada there was, until recently, (it is still marked on my map), a narrow gauge line which brought coal down from the mines at the head of the Sil valley. In the middle of the former industrial grot there is an unlikely looking skyscraper (pictured), more suited to Manhattan than a small Spanish town (for more about Ponferrada see Note 4).

After Ponferrada, near Bembibre, we see the main road and it is much busier than the deserted roads of Galicia, where driving must be a pleasure. For a while there is much evidence of the former coal industry and the map has plenty of mine symbols. There is a spiral section of railway line to gain height on this stretch, to cross the Montes de León from the valley of the Rio Tremor towards Astorga. At the head of the valley the railway is well away from the road and, in an isolated area, we cross the watershed into the area which (via its tributaries the Rio Orbigo and the Rio Esla) drains into the Rio Duero. At the foot of the mountains the land flattens and the line reaches Astorga.

From there it is a straight run over the plains of León past some low hills of soft yellow stone and into the city of León via a new stretch of track into a remarkably small modern, functional, terminus station. It has taken 4 hours 20 minutes from Lugo – a bargain at 14.60euros.

León

I chose León as a convenient place to stop for a night. We would have to change from rail to bus at that point and, as a historic city and provincial capital with a population of about 130,000 and the site of a major university it promised to live up to similar Spanish cities. Also, the first teacher who tried to teach me Spanish came from León and sang its praises.

The railway and bus station are on the opposite bank of the river Bermesa from the city centre but it’s not too far to walk to the modern centre, the Plaza Santo Domingo, then onwards into the casco antiguo (historic centre) along Calle Ancha. This pedestrianised shopping street was quiet at this time of day and leads to the cathedral. From there it is only a couple of more minutes to the Plaza Mayor. The square is impressive and my hotel is on the square itself, opposite the old town hall. Some rooms have balconies and a view looking out over the Plaza Mayor, but the cheap rooms are at the back, so I have a view of some air conditioning units. The room itself is fine, the bed is comfortable and tea and coffee are provided in the room.

It is a cool but sunny afternoon and I’m wrapped up well enough to have a couple of beers sitting outside the bar next door, watching the comings and goings. My tapita of peanuts is spotted within seconds, and is attacked by the square’s pigeons. Looking round there are quite a few bars on the square, and some of them look very much like late-night bars, so maybe I’m better off at the back of the hotel.

I have my usual walk around the area, having a cursory look at the main sights and taking some photos to prove that I’ve been in León. The Plaza Santa Maria de Camino is a lovely cobbled old square, with shady trees and an ancient small church. The back streets and the market area are quiet but atmospheric, there are plenty of shops which are permanently closed and a few abandoned buildings, but it looks as though it still has some life. By the time I reach Calle Ancha once more it is bustling with shoppers, and I wander on to have a quick look at the Basilica de San Isidro and the cathedral. I feel a bit guilty at not making the time to look inside the cathedral (the stained glass windows are meant to be particularly impressive) but I’ve always preferred just walking around to get the feel of a place. And there are many occasions when the choice is between the inside of a church and the inside of a beer glass, and the beer wins.

Much of the old town is known as the Barrio Húmedo (wet district) and it is full of bars. A little research came up with the Four Lions brewpub which I tried in the evening. At 8 o’clock it was already busy. It is an American style bar with excellent American Pale Ale (and several other beers) brewed on the premises, with the bonus of good quality jamon as the tapa. Later I tried the Cerveceria Celtica which has a huge range of beers both on draft and bottled. León clearly has a large student population and it was lively on a Tuesday evening. I only had the energy to sample a couple of places but I passed by quite a few that looked worth a visit if I’m ever back in the area. I might even have a proper look inside the cathedral and basilica if I do return.

Castilla y León

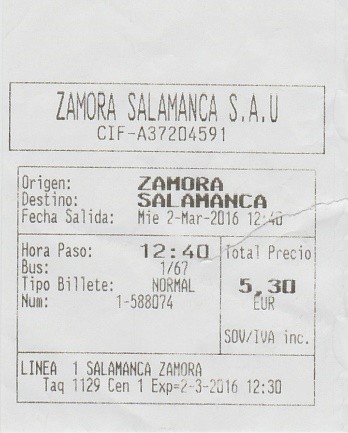

The Day Three journey is from León to Ciudad Rodrigo – about 275 km. There is no rail link so it involves three buses, operated by three separate companies, changing at Zamora and Salamanca.

It is 2nd March and the Spanish Cortes (parliament) is making a further attempt to form a government following inconclusive elections on December 20. Pedro Sánchez, leader of PSOE (Spanish Socialist Workers Party, roughly equivalent to New Labour), has been requested by the king to try to form a coalition government. Today is the first ‘investiture’ debate on the issue, and it lasts all day before an evening vote. Our driver to Zamora is obviously interested in politics, so for two hours the debate blares out from the coach radio as we trundle along the N630. It’s good for my Spanish to listen, but without TV subtitles stating who is speaking and from which party, it is easy to get confused. There is obviously bad blood between PSOE and Podemos (We Can, a much newer party, broadly similar to Corbynite Labour) which would be an essential partner in any left-of-centre coalition, so the prospects are not good.

The N630 is the old national route south from León, now paralleled by the A66 autovía or motorway, and it is a good road, now with little traffic. Branded ‘Ruta de la Plata’ (the silver route), because it broadly follows the Roman ‘silver route’ from the mines of Northern Spain to the Mediterranean, the A630 ran from Gijon on the north coast for 803 km to Sevilla (see Note 5). It is still there in parts, but 98% of the traffic takes the A66 autovía, which follows much the same route (and yes, I did see one café-bar called Ruta 66 in some out of the way village).

The first few miles were an endless strip of the industrial units, car and furniture showrooms, which blight the approach roads around many Spanish cities. The villages along the old road are deadly quiet and every so often there are abandoned service stations, truck stops, hotels and café-bars, no longer needed since the autovía took the traffic. The road follows the broad valley of the Rio Esla, but about a kilometre to the west is a very low ridge of soft yellow stone, every so often with a troglodyte village of cave houses built into the ridge. Local websites suggest that the caves were also used as bodegas to store wine when this was an important wine producing area. The modern village houses along the road are plain and brick-built and the area feels neglected.

After the main intermediate town, Benavente, the landscape became a little hillier with some woodlands together with grassland with oaks. Just before Zamora we passed a reservoir where the Rio Esla has been dammed, and crossed the line of the high speed railway from Madrid to Galicia (See Railway Buffery 2).

There was only ten minutes in Zamora to find the taquilla (ticket window) for the next journey and return down to the platforms to find the bus. The bus to Salamanca was much busier – it was 1240 and the morning shopping or studying has finished. Immediately we crossed the Rio Duero, which flows through Portugal as the Douro, on its way to the Atlantic at Porto. Once more we stick to the old road and, from time to time, the old railway line from Zamora to Plasencia can be seen. It looked as though they had just walked away from the line. The track was still in place (as were some colour light signals), and it still marked on the map, though it hasn’t been used for over 30 years and vegetation has taken over the line (see Railway Buffery 3).

We passed through a village called El Cubo del Vino, which, for me, translates as ‘the winebox’. The map shows many place names ending in ‘del vino’ but I saw no sign of growing grapes. A little research reveals that this was a major winegrowing area but many of the vineyards were wiped out by philoxera in the nineteenth century (see Note 6). Later we passed the large hilltop Topas prison, with a high concrete watchtower that can be seen for miles around.

There was a little more time to change buses in Salamanca, so I had a beer, and a freshly made Spanish omelette baguette, which looked tremendous but was far too salty. Like all the cities of Spain, Salamanca has vastly expanded as people moved from the surrounding countryside, extended families split into several nuclear family units, people sought larger apartments away from the crowded historic city, and industry and workshops sought modern premises. On the outskirts, between the residential areas are shopping centres, industrial units and endless ring roads carrying very little traffic. The economic crisis has intervened, and there are large areas laid out for housing or industrial purposes lying empty.

The El Pilar bus took the old road through the middle of nowhere. It is more or less a straight road for the 80 km to Ciudad Rodrigo (and a further 30 km to the Portuguese border) and the old road is sandwiched between the autovía and the railway. There were only a couple of small villages along the road, one of which gloried in the name of Sancti-Spíritus (see Note 7). I passed the third scrapyard of the day – they seem to take great pride in advertising their presence – with scrapped cars piled high. One had a rusting plane and a helicopter on plinths. The remainder of the immense plain was typical dehesa countryside of grassland and oaks and for the next couple of days this will be the predominant type of landscape.

In 2016 the railway line carried one train a day between the Franco-Spanish border and Lisbon calling at Ciudad Rodrigo at 0206 westbound and 0359 eastbound, so the choice to use the bus for this part of the journey was made for us. The train also carried coaches to and from Madrid and was the only remaining diect train between Madrid and Portugal – it has since ceased operation. It was about 1530 when the bus pulled into Ciudad Rodrigo and, as usual for this time of day, the bus station and town were deserted.

Ciudad Rodrigo

Ciudad Rodrigo, on a fortified hilltop site guarding a bridge over the Rio Agueda, close to the Spanish-Portuguese border, is another town where the walls have survived complete. These walls were built in the 12th and 17th centuries along with a substantial castle. The town was the site of sieges by the French in 1810 and the British in 1812. Today Ciudad Rodrigo is a town of 17,000 people and the centre for the local area.

The town has expanded beyond the walls but the old town is still the focus of most life, and even within the old town there has been more recent building. There has been little pressure on building land here so the outer defences – ramparts, cannon emplacements and the site of the moat – are intact, leaving a clear gap between the old and newer towns . Once again, our hotel, the Hospedería Audiencia Real is situated on the Plaza Mayor. At ground level all that can be seen is a door next to a bar, but upstairs it is a lovely small hotel. The friendly owner gives you your key to the outside door and instructions on using the heating system, and the next door bar can be used for evening meals or breakfast.

Wewalked around the streets of the old town and then round the walls. The Plaza Mayor is an impressive collection of buildings and is surrounded by streets of renaissance and baroque mansions and palaces. As well as the cathedral there are several other churches, whilst the castle has been converted into a parador hotel. The town was quiet but I was told that it is busy with tourists in summer. For some reason I could not see any stork’s nests in Ciudad Rodrigo – there are plenty in Salamanca, I saw some along the roadside from the bus and there are plenty of suitable towers for them to nest on.

There are a couple of café-bars next to the hotel and others on the square and in the surrounding streets so we tried a few. The evening’s tapas included excellent stuffed peppers. On every bar television the investiture debate was coming to a conclusion and in the vote Pedro Sánchez was unsuccessful…so there would be another debate and vote in two days’ time on Friday.

On to Extremadura

Another day and an early start to catch the 0830 bus back to Salamanca – it is a long way, and three buses to Trujillo. It was cold and clear and to set me up for the day I had a coffee and a tostada de tomate in the café-bar An-Mai on the Plaza Mayor (yesterday’s debate was being discussed endlessly by talking heads on the television – aargghhh).

From Salamanca, the next stretch to Cáceres is our longest coach journey. I meant to buy a ticket when we passed through yesterday but a beer and tortilla sandwich were more pressing. I was concerned that the coach might be full and it was 2½ hours until the next one. However, I managed to buy a ticket and the coach was fairly quiet. It was travelling from Valladolid to Sevilla, a nine-hour journey, and we were on board for the three-hour 200 kilometre stretch to Cáceres.

This coach is an express (and very comfortable) and we bowled along the A66 autovía. The hills became more substantial and, eventually, looming above Béjar, the northern face of the Sierra de Candelario was covered in snow. We called in at Béjar, an ugly town in a fine situation guarding the pass, and it was just past here that we crossed from Castilla y León into the region of Extremadura – the land beyond the Duero.

Shortly after the regional border we left the autovía and zigzaged down the old main road into Baños de Montemayor (pictured). This bus stops only at the principal towns, but this is a place I had never heard of. According to wikipedia.es it has a population of 774. The name gives it away – it is a resort based around thermal baths, one dating from Roman times. The town has plenty of hotels and hostals – presumably tourists are attracted to the spas, the equable climate and fresh air in the mountains. At this time of year there was not a soul in the streets or the tiny bus station.

Travelling, onward to Plasencia we passed through scrubby hills. Plasencia has endless apartment suburbs climbing the hills and we took a convoluted route through them to a bus station on the far edge of town.

The final stretch was along empty motorways through vast bare countryside. We crossed the main Madrid – Caceres – Lisbon railway line (though there are no passenger trains across the border these days). Alongside the motorway was construction work on the new high speed railway line which will reduce the isolation of Extremadura (see Railway Buffery 4). Apart from the transport corridor and the occasional cow or sheep the countryside is empty. Even when we crossed the Rio Tajo (the Tagus in Portugal, running past Lisbon to the sea) there was no sign of cultivation alongside the river, only an impressive new rail bridge under construction nearby (pictured).

We changed buses at Cáceres, where we had a tour of the ring road on both inward and outward journeys, and saw nothing of the town itself. The bus and train stations are close to each other on the edge of town. We did not visit the city on this trip this but I can recommend it from a previous visit in 1992 – the historic city centre is fascinating and the town is lively, helped by a large student population. I eventually located the taquilla for Trujillo – it turns out that Trujillo is the first stop on the 5 hour 10 minutes stopping bus route to Madrid (there are express journeys) – and, after a short break, off we went.

After we clear the modern university buildings on the edge of town there’s no sign of habitation until Trujillo. The first sight of the town is the castle and several churches on a hilltop. We arrived in Trujillo, drove straight through, and it looked as though we were about to head off towards Madrid – I would have been worried if there weren’t other passengers obviously planning to get off – when we pulled into a spanking new bus station on the far side of town. Ten platforms, one bus, and a café with a decent bottle of beer and the best wifi for several days. And it was much, much warmer than in Ciudad Rodrigo this morning.

Trujillo

From the bus station we made our way back into the modern town at the foot of the hill, then uphill to the historic centre around the Plaza Mayor. The square is extremely impressive with fine old buildings from the town’s richest period in the sixteenth century. Above the square several churches, towers and the castle add to the view. I sat and had a beer outside a café (it was definitely warmer) and watched not a lot happen, though there was a caravan in the middle of the square, which looked decidedly out of place, with an exhibition of new technology, which attracted the occasional curious local.

Most of the wealth of Trujillo was generated by the plunder of Latin America. The equestrian statue in the square is of local boy Francisco Pizarro, who led the conquest of the Inca empire (the statue was sculpted by an American in the 1920s). The largest mansion in the square is the Pizarro family home built with the proceeds. This area of Spain produced many of the conquistadores – they left here for the Americas, despite Extremadura being far from the sea. Maybe they were attracted to the adventure due to being raised in border country where violence was a way of life. Or, more likely, because Extremadura was a poor area and people heard stories of the endless wealth to be had in Latin America. Nevertheless, it explains the riches in the towns of this area, which otherwise is poor quality agricultural land with no mineral resources. Our hotel is in one of the palaces a little bit from the square. I could see storks nesting on a nearby tower and heard only the sound of birds when I opened the window.

Later in the day Ted and I walked up to the Moorish castle and battlements. It now stands at the edge of town, and beyond the final buildings. We returned downhill via the hilltop church of Santa Maria Mayor and took in the views over the surrounding countryside.

At night Trujillo is quiet. There are only a few tourists around in early March, though I imagine it is busy at summer weekends. It is a small town so not many locals to fill the cafes on the Plaza Mayor. The square is tremendously atmospheric at night with sensitive lighting and floodlighting adding to the scene. The gas heaters are lit outside the bars and I had a beer with a tapa of pork scratchings. Later, I had one of the most bizarre pizzas of my life. On a cheap shop-bought pizza base were mountains of a tasty mixture of chicken, goats cheese and caramelised onion. We headed inside for a final beer as the night was cold, then back to the hotel.

Trujillo to Mérida

We had time for a further walk round Trujillo in the morning. It was clear that, although most of the shops and banks are in the newer part of town along the main road from Cáceres, the Plaza Mayor and surrounding streets are still important. For breakfast we had another tostada de tomate in the bus station cafe then caught the bus to Cáceres.

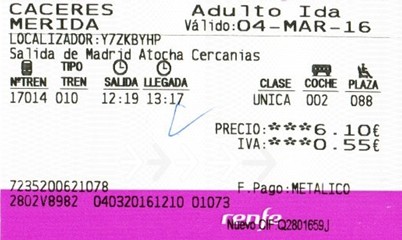

From now on we returned to train travel. It was shortly after noon on a Friday and, in the bus and train stations, it was clear that students were starting to move on their weekend trips home. However, the train from Caceres to Mérida was not too busy – the journey took one hour on a three coach Madrid-Badajoz regional train which has already taken over 4 hours from Madrid. If and when the new Extremadura high speed line is completed it will make a huge difference (See Railway Buffery 4).

The classic line was built cheaply with sharp curves, and towards Mérida there was a long stretch of jointed track in poor condition. The earth was red, there were some olive groves but most of the land was typical dehesa grassland with oaks, cattle and sheep. On one stretch we rattled along past black pigs snuffling on the ground for acorns and there were stork’s nests on the remaining telegraph poles along the line.

Extremadura region contains two provinces and during the journey we crossed the border between Cáceres and Badajoz provinces, before arriving in Mérida, the capital of the Extremadura region.

Mérida

It was still only 1310 when we arrived in Mérida so there was time for a walk round before checking in. Mérida does not have the sixteenth century grandeur of the conquistador towns of Trujillo and Cáceres, but it is a pleasant small town, much more southern in appearance than the other towns visited. on this trip. Today it is the capital of Extremadura and has about 60,000 inhabitants. The reason for visiting is that it was the Roman city of Emerita Augusta, capital of the Roman province of Lusitania (which covered Extremadura and most of modern-day Portugal). It is described as having more Roman remains than any other city in Spain and, as a consequence, it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

It would take several days to fully explore all the Roman sites so we took in only a few. Close to the station are the remains of a Roman aqueduct (with storks nesting on top of each remaining column). From there we walked down to the wide and shallow Rio Guadiana (which rises near Ciudad Real in central Spain and reaches the Atlantic as the border between Portugal’s Algarve and Spain). From the modern Lusitania Bridge, itself an impressive structure, there are good views of the Roman bridge, sixty arches long. We returned by the Roman bridge, which still forms a main pedestrian route between the two sides of town. Beside the bridge is a Moorish Alcazar, built on the site of a Roman fortress. Nearby, the main square, Plaza de España is a relatively plain affair but it is pleasant, there is space to relax, and we had a beer from a kiosk before finding our hotel.

Then we headed to the main Roman sites – the amphitheatre and theatre. It was quiet and there were only about ten of us exploring the large site, though the coach park nearby suggests it is popular during the season. The amphitheatre could hold 15,000 spectators for gladiatorial fights and other events. The theatre is an elaborate affair with two tiers of colonnades, and it is still used in the summer for performances. Near the exit is a row of Roman reproduction shops – Zambrano’s shop has the largest collection of Roman tat imaginable and I bought Ted a Roman column as a souvenir of the trip. Also nearby is the Museo Nacional de Arte Romano, meant to be very impressive, but it was time for food and drink in the row of decent tapas bars across the road and we decided to leave it to the next visit.

By evening it had turned cloudy with some slight drizzle, but it was a Friday night and the streets were busy. I saw from a Facebook post that it reached 29ᵒC on the Costa del Sol that day but it didn’t manage to rise above 13ᵒC in Mérida. In the middle of the Plaza de España there are four bar kiosks, one on each corner, so I followed the example of the locals and give each of them a try in turn. In three of them the tapita is olives and I’m all olived out by the end. There are no toilets in the kiosks, and I couldn’t see any public ones on the square, so it became necessary to find somewhere indoors. The evening finished in a bar close to the hotel. Inevitably, the second investiture debate and vote was on the television and, equally inevitably, Sánchez still did not manage to get a majority – he managed to get one more vote than on Wednesday, from a Canarian deputy. So there was a two-month break for negotiations before the next attempt to form a Government (or to call new elections).

In 2023, Ted and I were accompanied by our friend Ken and we took much the same route around town – we still didn’t manage to visit the Roman Art Museum. This time we found a couple of places selling craft beer, both of which are worth a visit – The Kraft Bar in Plaza de Pizarro and Cerveceria Bremen in C/ John Lennon. We also discovered that the kiosks in Plaza de España do actually have toilets.

Through Andalucía

A couple of café solos on the way to the station to catch the 0908 to Sevilla set us up for the day. Thankfully, it is Saturday – the train leaves at 0754 during the week. The train takes 3.5 hours for the 240km journey.

Outside Mérida something odd struck me about the landscape and I realised it was the first ploughed fields I’dseen in a few days. Then the olive groves appeared , together with a major olive pressing cooperative at Villafranca de los Barros. The olive trees were being pruned following the harvest in the winter, and fires had been lit to burn the cuttings. We also saw a few vineyards. The Tierra de Barros is described as the most fertile and prosperous agricultural area in Extremadura. The red earth looks rich, and some of the village houses look as though they have been built from the red clay. The village houses look Andalucian, with their internal patios obscured by the external walls.

The major town en route is Zafra, which we reached after 50 minutes on well-maintained track – there are only three trains a day but the time and price should be competitive with the coaches. Beyond Zafra station the line to Huelva (three trains a week, and therefore one of the obscure journeys I intended to do) heads off to the south. The route looked scenic from the map and we travelled on it in 2018 – see Journeys – Huelva and Badajoz . A freight line heads west to Jerez de los Caballeros – it appears that it is still in use and the map shows a couple of factories and a power station on the line.

Zafra is at the centre of a giant olive nursery, with acre upon acre of seedlings growing. We climbed gently and olives gave way to dehesa grassland and oaks with grazing sheep followed by rocky scrubland. Much of the land is used for hunting – we saw not only the usual ’coto privado de caza’ signs (private hunting land reserved for authorised hunters), but also the less common ‘coto social de caza’ signs.

At Llerena, a small town where the size of the church suggests it has been a place of some importance, the other two passengers in my coach disembark and we are alone for the rest of the journey. The stationmaster flagged us off – one train in each direction call at Llerena each day, but he has to sell the tickets and work the local points and level crossing, so it’s a busy day for him (though by the time we passed through in 2023 he seemed to have lost his job). The countryside then became mountainous as the line climbed. We passed a Moorish castle on the hill, and the map shows a Roman theatre nearby, so it is clear that this route has been important, linking Mérida with Sevilla and Cordoba. Fuente de Arco looked abandoned, but two people alighted into waiting cars – the village of 709 people, is behind a hill (see Note 8).

This is the most remote stretch of the journey as the line crosses the Sierra de Morena, and the watershed between the Guadiano and Guadalquivir river basins, at about 750m above sea level. Shortly after Fuente de Arco we left Extremadura and crossed into Andalucía and the province of Sevilla. The countryside is stunning – this is the Parque Natural de la Sierra Norte de Sevilla, part of the UNESCO Biosphere Reserve ‘Las Dehesas de la Sierra Morena’. The mountains are largely wooded and in the dehesa there are sheep, cows and black pigs grazing amongst the trees. The first stop in Andalucía is at the isolated village of Guadalcanal, which gave its name to an island in the Solomon Islands in 1568 (a local lad was on the expedition). Subsequently the island was the site of the first major Allied offensive against the Japanese in 1942-43.

Next is Cazalla y Constantina, a station in the middle of nowhere – the two villages are 8 and 12 kilometres away respectively. It is branded as a Cercanías (suburban train) station. I checked and two suburban trains make it up here from each day from Sevilla, keeping the stationmaster busy. I discovered later that the area, which had iron ore reserves (now exhausted) had Scottish connections (See Railway Buffery 5). As the train reached Pedroso, about 50km into Andalucía the dehesa begins to give way to olive groves, almond trees (in flower) and more intensive agriculture as we reached the plains.

At the foot of the Sierra Morena we are in the valley of the Rio Guadalquivir, the important river which links both Cordoba and Sevilla with the sea. The train calls at Villanueva del Rio y Minas – by now there are five suburban trains a day into Sevilla. The town coame as quite a shock – it was a coal mining and cement making town and the signs of this were everywhere. There was an old steam engine rusting in a siding (pictured below), the mine chimney and headgear still stand, and the town looks as though it has not recovered from the closure of the mines in 1972.

We crossed the river, passed through the agricultural town of Tocina and joined the old main line from Madrid via Cordoba to Sevilla at Los Rosales. It still did not look suburban, but after a further twenty minutes along the flat valley, and increasing urbanisation, we arrived in Sevilla Santa Justa.

The railway line is underused – In 2016 only one train a day travelled the whole route from Mérida to Sevilla. From Zafra to Cazalla y Constantina, the most scenic stretch of the route, it was the only service. The railway cannot compete with express coaches along the more direct autovía (the fastest of the 8 services each day from Mérida to Sevilla takes two hours). However, though there are some slow stretches with 60 or 70 km/h restrictions due to poorly maintained track or risk of landslip, the majority of the line is in good condition, at least as good as a rural UK line. On the most scenic stretch of the line I estimate there was no more than fifteen passengers on the train. When we travelled from Sevilla to Mérida in 2023 there had been some improvements to the line, but not the frequency of trains, though our Friday afternoon train was quite busy with people heading home for the weekend. By 2025 the frequency had been doubled two two trains a day and a day return trip is now possible in either direction bewteen Zafra and Sevilla. It seems a waste of its tourist potential that the route is so poorly marketed (see Railway Buffery 5).

It was only 20 minutes until our next train departed for Málaga. This train was quite busy and all the stations we call at had passengers waiting. We have travelled by train from Sevilla to Málaga many times so I dozed for part of the journey. On the train there were people speaking English and I realised that it was the first I’ve heard since the flight to Santiago. Coming after a few days further north it was striking just how Moroccan the small towns look. I realised that I had never stopped in Marchena or Osuna (I visited the latter the following year), both of which looked as they could be interesting, with glimpses of the historic areas from the train.

The Andalucian Government started to build a new high speed line from Sevilla to Granada, and there were plenty of signs of its route. The track-bed is complete but sits there without track and unused – work was stopped during the economic crisis and has never restarted (see Railway Buffery 6).

Bobadilla, where lines from Málaga, Algeciras, Sevilla, Madrid and Granada meet, has lost much of its role as the Crewe Junction of Andalucía since the Madrid – Málaga high speed line was opened and much of the traffic now calls at the nearby Antequera-Santa Ana. station. Between Bobadilla and Málaga the railway had to find a route through the mountains. After the longest tunnels there are a series of short tunnels between which there are spectacular views of the El Chorro gorge, and the Caminito del Rey, the walking route along the sheer side of the gorge. Unused for many years the path has been repaired and reopened and people wave to the train from the path. This stretch of line makes it well worthwhile to take this route rather than the faster high speed trains between Sevilla and Málaga – it also gives a view of the impressive viaduct on the new line near Alora.

We arrived at Málaga Maria Zambrano, then the final stretch of our journey was a suburban cercanías train to Benalmádena-Arroyo de la Miel and home. The journey took from Monday morning to Saturday afternoon and we travelled just over 1200 kilometres from Santiago de Compostela airport at a cost of 127.19 euros in train and bus fares. More important than those statistics, there are none of the journeys and none of the towns that we visited which I wouldn’t recommend. Like most of my trips I treated it as a recce, to find places that I would happily go back to and get to know better (nothing to do with intimations of mortality and trying to cram as much in as possible before I reach my dotage) and everywhere I visited falls into that category.

Railway buffery

1 Lugo to León

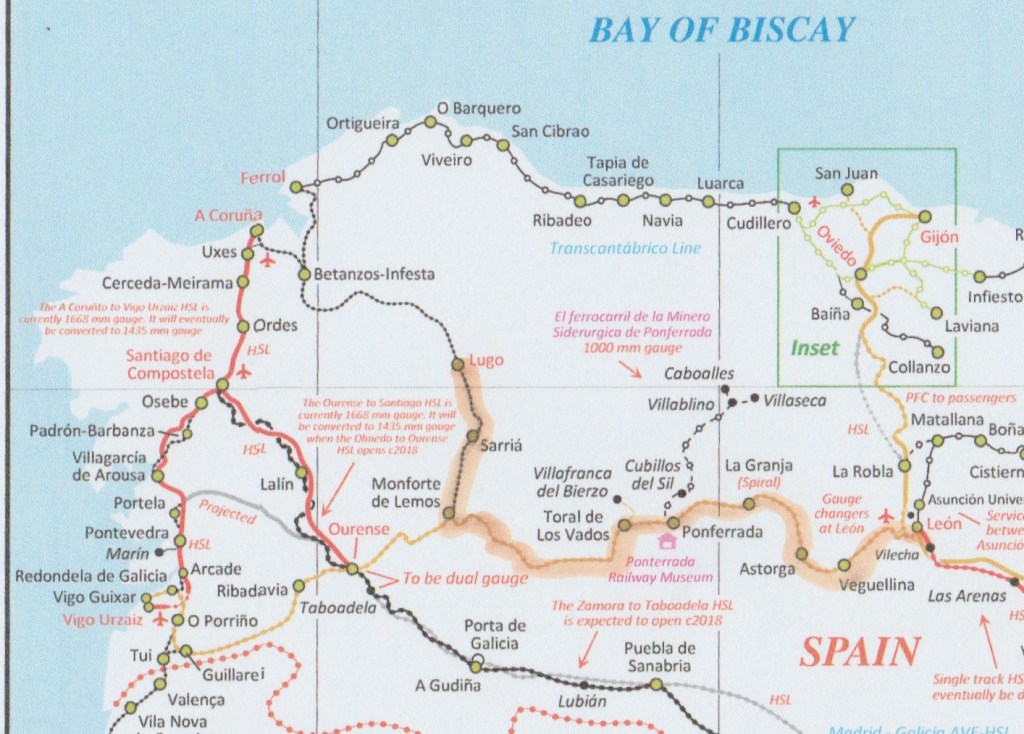

The railway between León and Lugo opened between 1878 and 1883 as part of the first link between the rest of Spain and Lugo. By 1913 the fastest train of the day took 8½ hours between the two cities. Today the Lugo – Monforte de Lemos section is part of the route from A Coruña and Ferrol to Madrid. From Monforte it continues to Ourense where it joins the lines from Santiago de Compostela and Vigo. The Monforte de Lemos – León section is part of a route that links Galicia with the Basque Country and Catalonia.

The timetable from Lugo changed in February 2016, following the opening of a further stretch of LAV (Linea de Alta Velocidad) high speed line from Olmedo to Zamora, since extended to Ourense. The difference LAV lines make is illustrated by the fact that in 2025 the Alvia train from Lugo to Madrid takes 4 hours 42 minutes for the journey. The 118 kilometres from Lugo to Ourense takes 1 hour 39 minutes (average speed 71.5 km/hr) and the 547 kilometres from Ourense to Madrid takes 3 hours 3 minutes (average speed 179.3 km/hr).

The construction work taking place on the line between Monforte and Lugo in 2016 was a much reduced scheme to make the line compatible with higher speed trains by improving the slowest stretches of the route.

The narrow gauge line from Villablino at the head of the Sil valley ran for 64km to Ponferrada, where it met the Monforte – León main line. The line and its branches were built primarily to exploit the coal reserves of the valley and bring the coal to Ponferrada, where it was washed and/or transferred to the main line for onward distribution. More recently, the line was used to take coal to major power stations in the valley. There was a passenger service on the line until 1980 – when it ceased it was the last steam worked line in Western Europe carrying three classes of passengers. Coal traffic ceased more recently and much of the line is still in place. There was talk of re-opening part of the route as a tourist heritage line (which hasn’t happened), or converting the track-bed into a footpath.

The current León station opened in 2011 as a provisional station, replacing the Estación del Norte. This replaced a through station with a terminus station where through trains have to reverse. The high speed line from Madrid reached León in September 2015, with the conversion of two of the four platforms to standard gauge and the installation of a gauge changer outside the station for trains between Madrid and Asturias. New underground through platforms were opened in 2021 as part of the extension of the high speed line to Asturias. Much of the new line between León and Oviedo will be in tunnel under the mountains – the long Pajares tunnel replacing the scenic mountain route opened in November 2023.

2 Madrid – Galicia High Speed Line (LAV)

The high speed line between Zamora and Ourense was planned to open in 2018, completing the LAV link between Madrid and Galicia. The section from Madrid reached Zamora in early 2016, trains using a gauge changer to continue on the existing line towards Galicia. The Zamora – Ourence section opened at the end of 2021. From Ourense the line to Santiago de Compostela, A Coruna and Vigo was already open.

3 Astorga -Zamora – Salamanca – Plascencia line

The Astorga – Zamora – Salamanca – Plascencia line was opened in 1896 as a link between the regions of western Spain. In its latter years, despite re-signalling, the poor quality of the track and lack of investment in maintenance led to speeds declining. Many sections had speed restrictions of 50 km/hr or less, and the line could not compete with road traffic. The line has been out of use since 1985. Campaigns to reopen the line have been unsuccessful and lifting of the track began in 2013, with the aim of converting some of the route into a ‘via verde’ long distance foot and cycle path.

The name ‘Ruta de la Plata’ was also used for the railway and for the through trains, pictured above, which used the line to travel between Sevilla to Asturias. In its final year of operation the daily ‘fast’ train from Sevilla to Gijon via this route took 15½ hours. From Salamanca to Cáceres (less than three hours by coach today) the fast train took four hours and the stopping train took more than 6 hours.

4 Madrid – Extremadura – Lisbon

The daytime train from Madrid to Lisbon, which took about 9 hours for the journey ceased to run around the turn of the century. The overnight train via Extremadura was cancelled in 2012, leaving no trains to Portugal via this route. The current coach time between the two capitals is about 8 hours.

A high speed line (LAV) between Madrid and Lisbon was planned jointly by Spain and Portugal with the aim of reducing the time between the two capitals to 2 hours 45 minutes, which would make centre to centre journeys competitive with air travel. Work on the route began in Spain in 2008. However, the Portuguese government cancelled their high speed programme in 2012. The high speed line is now planned to run from Madrid to Badajoz, near the Portuguese border, via Cáceres and Mérida. The stretch from Plasencia to Badajoz opened in 2022. It is currently estimated that it will be 2030 before the Madrid – Plasencia section is built.

5 Mérida – Zafra – Sevilla.

The line from Zafra to Sevilla was eventually completed in 1885, opening up links between the Extremadura network and the port at Sevilla and assisting with the exploitation of the mineral resources of the Sierra Morena. By 1913 the fastest of the three daily trains between Mérida and Sevilla took 9 hours. The through service on the route is currently (2025) two daily trains, increased from a single service when we took this trip.

Fuente del Arco was a junction station with a metre gauge line, which reached Peñarroyo by 1895 and Puertollano by 1924. It was built mainly for freight – there are iron and coal deposits along the route. The line carried passengers from 1902 until its closure in 1970. In 1913 the fastest of the three daily trains took 3 hours to travel the 43 miles to Peñarroyo.

Near Cazalla y Constantina station (pictured) was a junction with a standard gauge freight line from the iron ore and mineral workings at nearby Cerro de Hierro. The mines and the line were owned by William Baird Mining, a coal and iron ore company originally based in Coatbridge, Lanarkshire. The mines closed in 1985 and the railway route is now a walking and cycle path. Following nationalisation of their UK coal and steel interests William Baird diversified into textiles, including the purchase in 1981 of the raincoat manufacturers Dannimac. Source: www.gracesguide.co.uk

6 Sevilla – Granada High Speed Line (LAV)

The Andalucian Government planned a high speed rail route crossing Andalucía from Huelva via Sevilla, Antequera, and Granada to Almeria. It currently seems unlikely that the entire route will be built in the near future, if ever. Construction work was begun on the Sevilla – Antequera section and much of the track-bed is complete. Work on this section was cancelled when the economic crisis struck Spain and the Junta de Andalucía has still to secure funding. Funded by central government, the section between Antequera and Granada has opened, giving Granada improved links with Madrid.

Practical information about the trip

Hotels

I used the following hotels:

Lugo: Hotel Méndez Nuñez ****

León: NH Collection León Plaza Mayor ****

Ciudad Rodrigo: Hospederia Audiencia Real **, now the Hotel Palacio Antigua Audencia

Trujillo: NH Trujillo Palacio de Santa Marta ****, now Eurostars Palacio Santa Marta

Mérida (2016): Hotel Rambla Emerita ** ; (2023): Hostal La Flor de Al-Andalus *

All were good value for money (Ciudad Rodrigo was excellent for the price) even as a single traveller, much cheaper than comparable accommodation in the UK. I used the NH website www.nh-hotels.com and booking.com for the others. I booked room only – there is always a cafe-bar nearby for breakfast, except for Lugo where an (excellent) breakfast was included in the price. All were very central, but with quiet rooms. León, Ciudad Rodrigo and Trujillo were in historic buildings. All of them had free wifi – useful as the internet signal was poor on some stretches. All of the towns except Lugo have parador hotels, all of them in historic buildings, which would be an excellent, albeit more expensive alternative.

Information and sources

To plan the trip and identify which places I wished to see I used the Rough Guide to Spain to help choose. A couple of options were dropped due to inconvenient or non-existent train or bus connections.

Both for planning purposes and during the journey I used Michelin 1:400,000 regional maps of Spain. They are good at indicating scenic routes, and rail lines as well as roads are clearly mapped (and they are cheap). The relevant maps are numbers 571 (Galicia), 575 (Castilla y Leon), 576 (Extremadura) and 578 (Andalucía). The Michelin Motoring Atlas of Spain and Portugal uses the same mapping. Google maps was useful for arriving in the towns, as train and bus stations can be well away from the modern or historic town centres (and the hotels).

For post-trip research and fact-checking Wikipedia and the Spanish language counterpart Wikipedia.es were the starting point. Local council websites (usually municipio or ayuntamiento de the place name) were also useful. Even the tiniest municipalities (and there are plenty of them) are likely to have a website. For the railway buffery section additional sources of information were the Ferropedia site – now www.ferrocarriles.fandom.com , www.spanishrailway.com (in Spanish despite the English name), and the reprint of Bradshaw’s Continental Railway Guide 1913 (the one that Michael Portillo used while traipsing around Europe). Any mistakes in translation from Spanish sites are mine.

Travelling by train and bus

Most trains in Spain can be reserved in advance, though reservations are generally available up to the time of departure. Most longer bus routes can also be reserved online or at ticket offices in advance. Provided Friday and Sunday afternoons (and Spanish holiday periods) are avoided, turning up and going is not a problem.

Almost all train services are operated by RENFE, and times and tickets are available on www.renfe.com and the Renfe app. The Man in Seat 61 www.seat61.com includes much useful information about travelling by train in Spain.

Bus services are operated by a multiplicity of companies. Company websites and apps are of varying quality, from the OK to the dire. At bus stations each company has its own ticket window (taquilla) which needs to be located. A wave of takeovers in recent years hasn’t helped as online information and local people may know the company by its former name. Services between main towns are pretty good, and comfortable coaches are used. Long distance coaches (on this trip from Salamanca to Cáceres) may have wifi and entertainment systems.

The companies used on this trip and their websites are:

* Santiago de Compostela – Airport – Lugo: VIBASA http://www.monbus.es

* León – Zamora: Empresa Vivas www.autocaresvivas.es

* Zamora – Salamanca: Zamora Salamanca www.zamorasalamanca.es . Alsa http://www.alsa.es operate a couple of through journeys each day León – Salamanca, but most journeys connect at Zamora where you have to change bus and buy a new ticket.

* Salamanca – Ciudad Rodrigo: El Pilar Autocares www.elpilar-arribesbus.com

* Salamanca – Cáceres; Alsa www.alsa.es

* Cáceres – Trujillo: Avanzabus avanzabus.com and Alsa alsa.es both operate on this route.

Buses can also be booked through the Movelia site movelia.es though when I checked the information for the Leon – Zamora – Salamanca journeys was incomplete.

Notes:

[1] Wikipedia confirms the role of horreos. Though mainly concentrated in Northern Spain and Portugal there are examples from other parts of Europe (including Switzerland where they are known as raccards). The staddle stones on top of the pillars are what prevents the vermin reaching the grain.

[2] This route passes through León and Ponferrada (see Lugo to Leon section), and pilgrims form a significant proportion of tourists to these places. A subsidiary route known as the Via de la Plata, commences in Sevilla and basically covers this trip in reverse…so scallop signs were a regular feature by the roadside throughout our journey

[3] This area is known as Valdeorras which is also a wine denomination. Once over the border into León the wine region is the Bierzo. The industry on this stretch is slate mining and processing.

[4] According to Wikipedia Ponferrada has about 67,000 inhabitants. It was the base of Minero Siderúrgica de Ponferrada (Ponferrada Mining Iron and Steel Co), founded in 1918, which became Spain’s largest coal mining company. It also became a major base for electricity generation and power stations remain nearby. Since the closure of the coal industry it has attracted a university and tourism – it is on the Camino de Santiago. The skyscraper is the Torre de la Rosaleda, the highest building in the Castilla y León region. In 2012, three years after completion, it was still largely empty, leading Spanish newspaper El Pais to re-name it the Torre de la Burbuja, tower of the (property) bubble.

[5] I later find it suggested that ‘plata’ is a mistranslation of an Arabic word ‘balath’, meaning paved (Roman) road – but it is the ‘silver’ meaning which is in common use.

[6] The population of El Cubo del Vino is less than half of what it was 100 years ago. There have been attempts to revive viticulture and in 2007 the Denominacion de Origin for Tierra del Vino de Zamora was secured. It covers a wide area and www.tierradelvino.net indicates that there are 6 wineries producing the D.O. wine, though none are located very close to the N630 road.

[7] As an example of Spanish rural depopulation as people flocked to the cities, the population of Sancti-Spíritus was 2420 in 1950. It is now 879. This decline is quite typical of the villages I researched on Wikipedia following the trip.

[8] The population is down from a high of 2652 in 1950. The figures show that 13 of them live by the station, but there is no sign of any of them.

Links

If you are interested in visiting these areas of Spain you may wish to look at the following pages on the site from our travels: Our 2014 visit to Galicia travelling along the North Coast from Santiago de Compostela The Galicia trip ; Our 2018 trip by train from Huelva to Merida and Badajoz Journeys – Huelva and Badajoz ; Our second visit to Merida in 2023 en route from Sevilla to Badajoz and on to Portugal The Portugal Trip . We have visited Sevilla many times, most recently in 2025 and the site includes a guide to the city Guide to Sevilla .There are also some photographs of our earlier visits to Santiago de Compostela, Zamora and Salamanca in Spanish Miscellany .

Copyright and Credits

Copyright © Steve Gillon 2016, 2023 (Mérida update), 2025 information update and additional photographs),

The map at the top of the page was drawn on a base which is copyright © 2009, National Geographic Society, Washington DC. The two maps of the railway journeys are from the European Railway Atlas by MG Ball, 2016 edition.

Photograph credits:

All photographs are by Steve Gillon, except for the following which were sourced via Google Images:

Galician hórreo: Wikipedia; Torre de la Rosaleda, Ponferrada: from www.ileon.com, photo by infobierzo.com; Rio Tajo bridge: www.hoy.es ; Black pigs: www.seriouseats.com ; Sevilla Santa Justa Station: http://www.thetrainline.com ; Malaga Maria Zambrano Station: http://www.seat61.com ; Villablino-Ponferrada steam train – Ferropedia ; Ruta de la Plata railcars: www.afzamorana.es ; Cazalla y Constantina station: http://www.abc.es/sevilla ; RENFE train: www.rondatoday.com